Added 1 new A* page:The galaxy I was talking about yesterday, NGC 3115, in which hot gas has for the first time been observed falling into a black hole (and a 2-billion-solar-mass supermassive one, at that), is a lenticular galaxy; lenticular galaxies are disc-shaped like spiral galaxies such as our own Milky Way, but don't have clearly defined spiral arms; they also tend to be brighter and to have larger central bulges than spiral galaxies. Since they don't have the spiral star formation areas of a spiral galaxy, they have less ongoing star formation, and tend to consist of older, redder stars. There have been theories that lenticular galaxies are old spiral galaxies whose arms--the primary star-forming regions--have used up all their gas in star formation; however, the greater brightness and larger central bulge of lenticulars suggest that there is more to their formation than just fading from a spiral. Another theory is that they're the result of a galactic collision or merger that sucked the gas away from the original spiral arms, but the bulge and the types of stars they contain don't make them an easy fit for that model, either.

I've mentioned a lenticular galaxy before, which also happens to be the largest known galaxy in the universe: IC 1101 weighs in at about 100 trillion solar masses--our spiral Milky Way galaxy, by comparison, has 0.25 trillion. So those lenticulars must be doing something right. I've got a couple pictures of IC 1101 in the post I made about it in February.

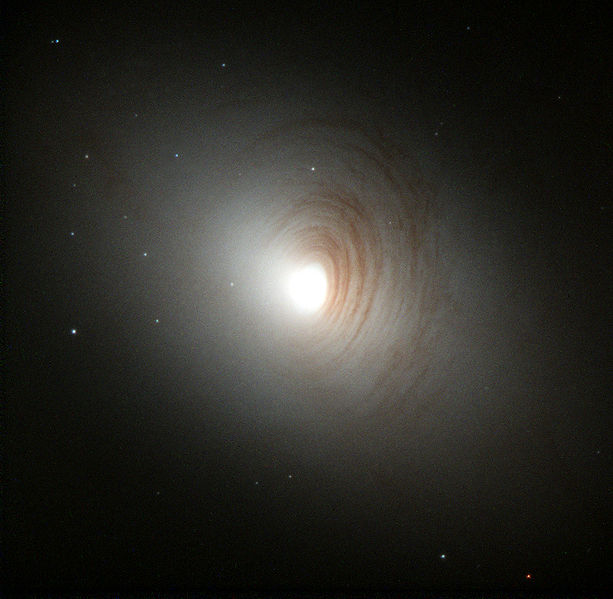

IC 1101 may be a bit bland-looking for all its size, but don't let that make you think that all lenticular galaxies are dull. For instance, the lack of spiral arms makes the bands of dust in NGC 2787 (a barred lenticular galaxy about 24 million light years away) stand out in rather impressive fashion, as captured by Hubble in 1999:

image by NASA (source)

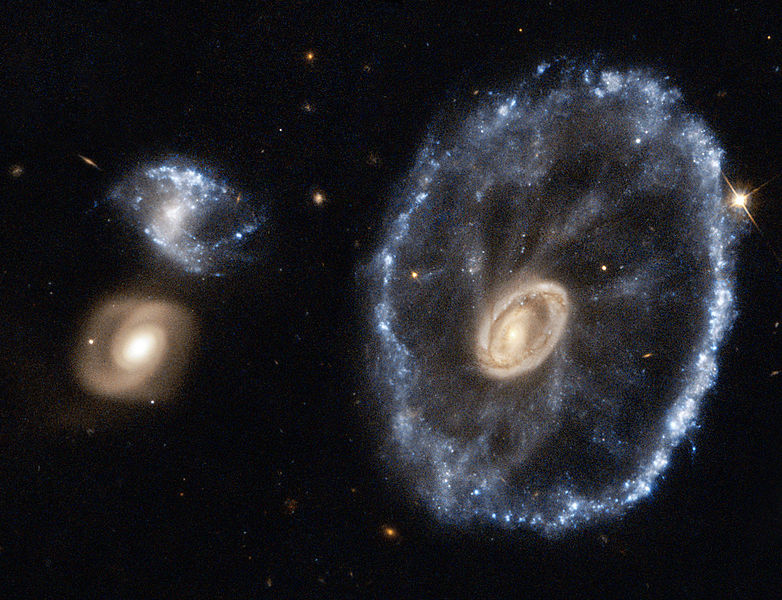

Further afield at 500 million light years distant, but even more spectacular, is the Cartwheel Galaxy:

image by NASA/ESA (source)

The Cartwheel pretty definitely *is* the result of a galactic collision--probably with one of the two smaller galaxies to its left, or a third candidate galaxy not in the frame, which would have passed through the center of the larger galaxy. The collision produced two waves of intense star formation, now visible as an inner orange ring and outer blue ring; the outer ring is about 1.5 times the size of the Milky Way. But for some real fireworks, lets look at it in a composite of different wavelengths:

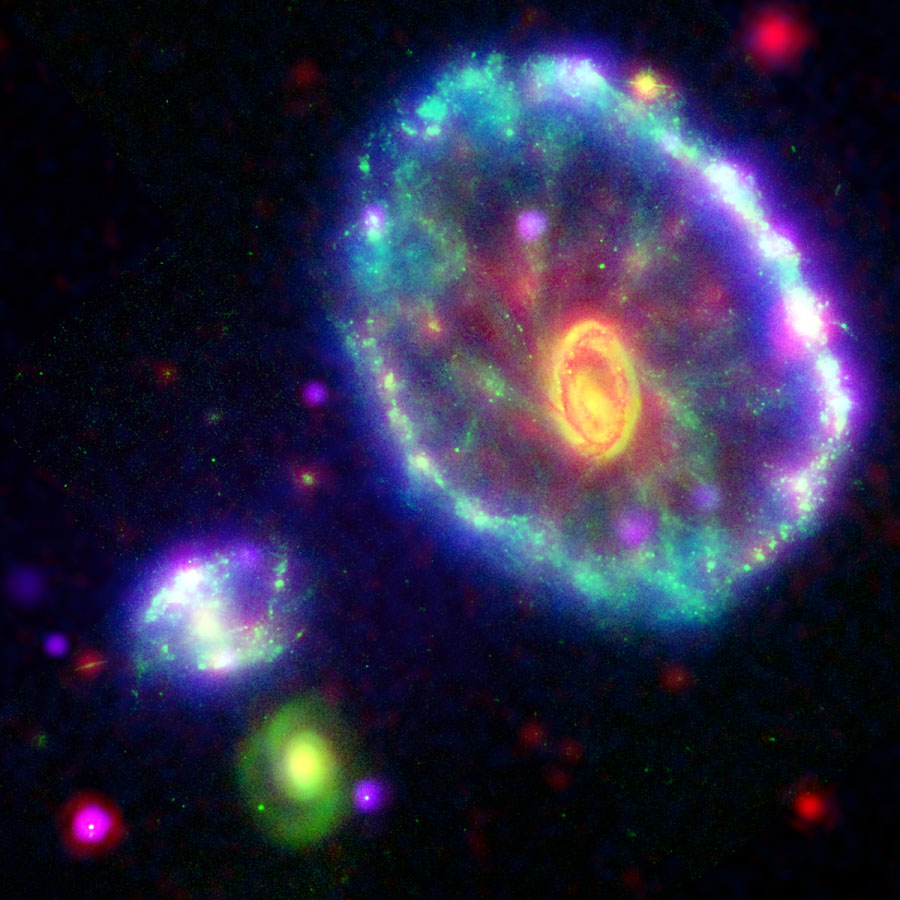

image by NASA/JPL-Caltech/P. N. Appleton (SSC/Caltech) (source)

^ That's blue for ultraviolet (from NASA's 2003 Galaxy Evolution Explorer satellite, or "GALEX"), green for visible light (from Hubble), red for infrared (from Spitzer), and purple for X-ray (from Chandra). For our purposes, the pink areas around the outside of the Cartwheel are the most interesting: those are areas of both high ultraviolet and X-ray emission, likely being generated by material being sucked off binary companion stars by stellar black holes. The blue ultraviolet of the outer wheel as a whole suggests that that intense star-forming region is creating large stars, 5-20 times the mass of the Sun. The orange center is visible and infrared emissions from the second wave of star formation; the green areas are older, less massive stars, whose primary emission is in the visible spectrum.

|