Added 1 new A* page:Well I've been talking about discoveries made by Skylab in recent posts, but I've never actually dedicated a post to Skylab itself (ie a post in which I summarize Wikipedia's Skylab entry for myself :p), so maybe it's due!

Oh first though I have to remind you, fair reader, about my weekend fairy tale comic, The Princess and the Giant, which updates Sundays, this weekend being no exception. So look forward to a new page of that, and if you need catching up, here's a link/preview to/of last week's page:

~~~~~~~~

Okay, Skylab!

image by NASA (source)

After the Apollo program succeeded in landing men on the Moon in the late 60's, NASA knew they'd have to find something else to do with the people and hardware that had been put to work in Apollo. One thing they came up with was using the workhorses of the Apollo program, the mighty Saturn V rockets, as carriers of space station components that would be designed to fit neatly into the shell of one of the rocket's sections; this type of scheme actually went back to ideas that German scientist and "father of American space flight" and all that, Wernher von Braun, had submitted as far back as 1959. A station based on this type of scheme was developed, and the result, Skylab, launched into Earth orbit on a modified Saturn V rocket in 1973.

It ran into trouble right away, though: during launch, wind resistance tore off the station's micrometeoroid shield, damaging the tie-downs holding one of the station's solar panel arrays, and an exhaust plume from a separation rocket fired during one of the later stages of the launch sequence hit the partially deployed solar panel, effectively destroying it. The station made it into orbit, but without its shield, which had also been intended to reflect away some of the heat of the Sun, the interior temperature rose to an uninhabitable 126 degrees F. And the accident in which the shield was lost had not only led to the destruction of one of the solar arrays, but had also caused the other solar array to be stuck pinned to the side of the station, so the overheated station also had a significant power deficit.

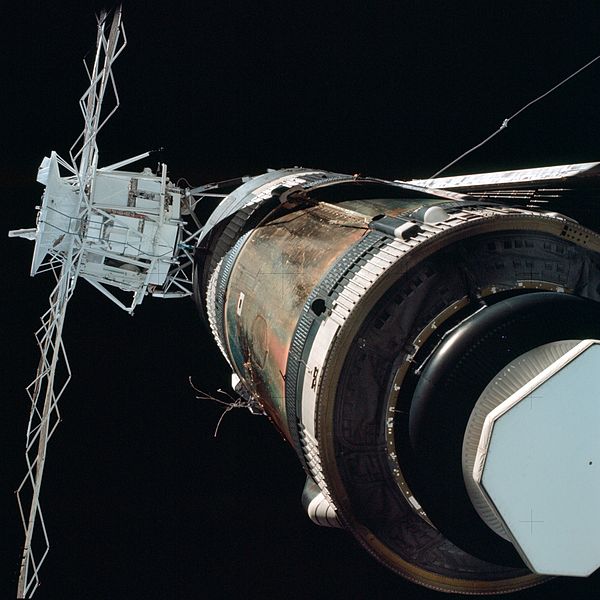

The heating was the most immediate problem, as the station would soon get so hot that its plastic insulation would melt, filling the interior with poisonous gas. NASA scrambled and launched a repair mission just eleven days later. Flying around the station in an Apollo Command/Service Module, this is what the three-man crew of the repair mission saw:

image by NASA (source)

^ The torn cables and tubing sticking out on the left side show where the shield had been torn away, exposing that large copper-colored surface. And you can see the jammed solar array on the right-hand side.

To fix the overheating problem, the crew of this repair mission deployed a gold "parasol" over the area originally intended to have been covered by the shield; you can see it in the first photo in this post, toward the bottom of the fuselage; you can also see there the solar array that was pinned now fully deployed (a second spacewalk two weeks later freed it, and finally got sufficient electricity flowing through the station), and (I think) the vacant spot on the other side of the fuselage where the other array would have been, had it not torn off during launch.

With the station habitable again, that crew was able to spend a few weeks engaged in research experiments, including the first detailed observations of the Sun with Skylab's instruments (more on that in the post linked at the top of this article!). In all they spent 28 days in space, which was a record for the time. Two more crews would work in Skylab over the next seven months, each setting a new record for time in space: 59 days for the second crew, and 84 for the third.

By Apollo standards, Skylab's interior was pretty plush. They had a full-sized shower, seen enjoyed here by a member of the second crew

image by NASA (source)

(^ That image is from NASA's Great Images in NASA gallery; I posted some of my favorites from it on the A* forum some time ago--check 'em out, there's great stuff in there.)

Eventually though the crews found showering, drying, and vacuuming away the excess water in zero gravity rather difficult, and settled for just using damp washcloths instead. There's also an interesting note in the Wikipedia article that crews found bending and sitting in zero gravity puts an uncomfortable strain on stomach muscles--without gravity, you have to use your abdominal muscles to stay bent over... So in space, sitting is how you get really chiseled abs, maybe. Or maybe you just get really sore. Here's a mockup of the Skylab dining area from a Smithsonian exhibit; I guess the manikin isn't quite in a full sitting position:

image by Steven Williamson (source)

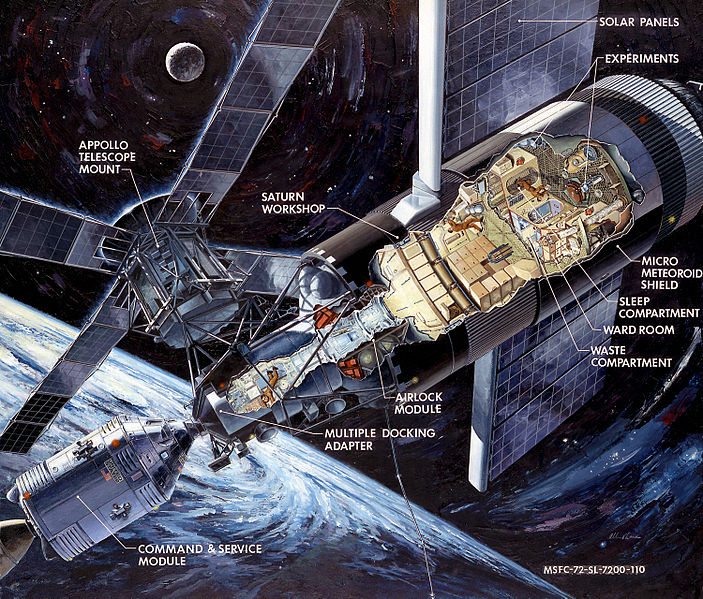

Here's a 1972 NASA diagram of what it was supposedly all going to look like when inhabited; you can see that the big telescope is in the X-shaped solar array, that Apollo CSMs would dock at that end, and that yep, there would have been the second side solar array opposite the first, if it hadn't been torn off during launch (the "APPOLLO" typo is also fun :D--ooh, rocket science!):

image by NASA (source)

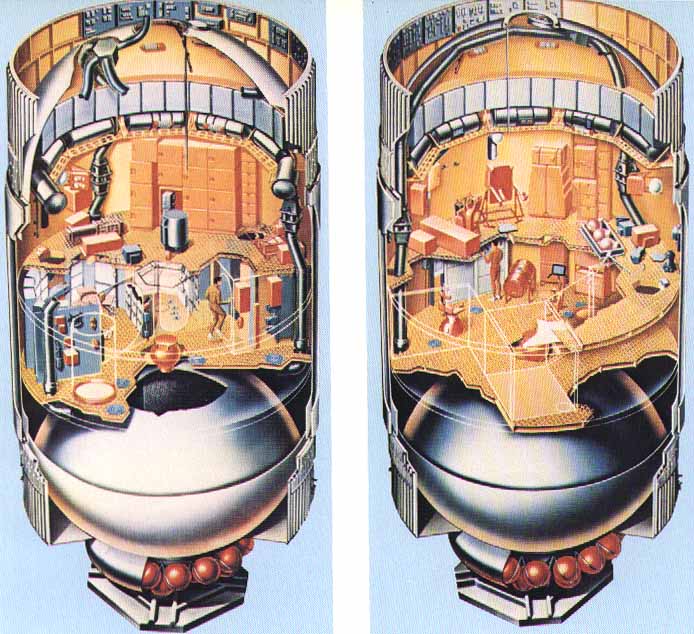

And another diagram detailing the interior:

image by NASA (source)

Quite roomy by space program standards!

Skylab had launched in May 1973, and after those three manned missions, by February 1974, NASA felt that the station, over a year old, was getting too old to be safe for habitation--which seems like a quaint notion nowadays since we're used to say the International Space Station staying up there for years and years, but such was the feeling at the time. But with the Space Shuttle due to be ready in '79, subsequent studies concluded, by '78, that the station, now abandoned for four years, should still be inhabitable ("It still had 180 man-days of water and 420 man-days of oxygen, and astronauts could refill both; the station could hold up to about 600 to 700 man-days of drinkable water and 420 man-days of food"), and a gyroscope that had failed in the interim should be repairable; furthermore, the last crew on the station had boosted the station to an orbit 6.8 miles (10.9 km) higher, which was supposed to keep the station at a relatively stable orbit until at least the early 1980's. Shuttle missions could refurbish the station, and boost it to an even higher orbit, further extending its operational life.

But the Space Shuttle was delayed (the first Shuttle wouldn't launch until 1981), and then it became clear that the station's orbit would not last as long as had been forecast; ironically enough, an unexpected increase in solar activity--that field in which Skylab research had played such a key role--caused increase heating of the upper atmosphere, and thus higher drag on the station, causing it to slow--and thus fall. This increased solar cycle had been predicted in 1976 by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, but NASA had apparently ignored this, and instead had used what one NOAA scientist called an "inaccurate model" for predicting the solar weather and its effects. And even by late 1977, NORAD was able to predict that the station would re-enter the atmosphere in mid-1979.

NASA had been working on a booster system Shuttles would have attached to the station to boost it to a higher orbit, but it wasn't quite complete, even if they had been able to get some rocket missions ready to take it up to the station. There was nothing for it: Skylab was going to come down, and an international media frenzy began, with bets on where and when it would fall, and contests to be the first to recover pieces. Skylab re-entered the atmosphere on July 11, 1979. NASA tried to aim it for a spot in the ocean off South Africa, but their calculation of how fast it would burn during re-entry was off by 4%, and so pieces instead landed in Australia (NASA had also predicted that the chances of debris hitting a human being were "only" 1 in 152); some debris landed in the Shire of Esperance in western Australia (you know, it had never really occurred to me to consider that there are "shires" outside of Tolkien, such has been my isolation in shire-less regions of the US of A), who in retaliation fined the United States $400 for littering, which of course our government did not deign to pay--but finally in 2009 an American radio host "raised the funds from his morning show listeners and paid the fine on behalf of NASA." Aw.

Such is the saga of Skylab!

|