Added 1 new A* page:Turns out that today's (Friday's) launch of the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer--an instrument that will be placed on the International Space Station to look for crazy stuff like antihelium and theoretical neutralinos in cosmic rays--(I blathered about this earlier in the week) has been delayed; according to the AP article, the launch was called off due to a few technical issues in its launch vehicle, the Space Shuttle Endeavour: "one of the two prime heaters for a fuel line feeding one of Endeavour's three auxiliary power units failed" and "another heater was acting up." Monday will be the earliest date on which they could try again, but it may take longer than that to get things squared away. It's to be Endeavour's last flight anyway as the Space Shuttle program winds down; Endeavour, first flown in 1992, was the shuttle that replaced Challenger, which broke up during launch in 1986, resulting in the death of all seven crew members.

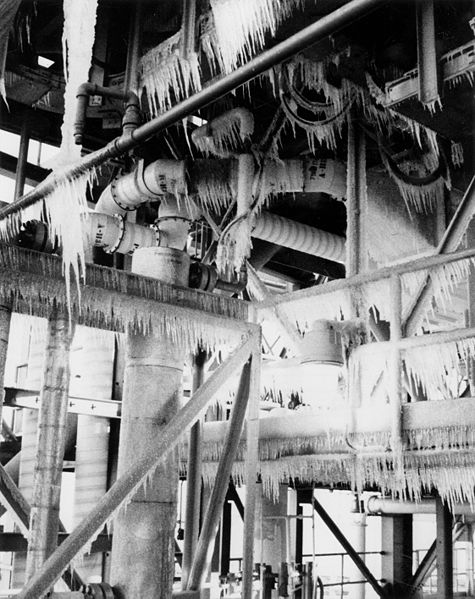

The Wikipedia article on the Challenger Disaster is a morbidly fascinating read. The launch--scrubbed multiple times already due to bad weather and minor mechanical problems--took place on an unusually cold January 28th: overnight lows of "18 °F (−8 °C)" meant that launch temperatures would almost certainly be below the "redline" 40 °F (4 °C) temperatures established for the Shuttle's solid rocket boosters ("SRBs"). Check out how much ice had accumulated beneath the launch pad:

image by NASA (source)

Furthermore, they knew that they did *not* have data on how well the rubber "O-rings" sealing three of the joints holding the six sections of each SRB together would function in temperatures below 53 °F (12 °C); the O-rings were designated as "Criticality 1" components, meaning that their failure would result in the loss of the vehicle and death of the crew, yet they could not be assured of them functioning properly in the frigid conditions at the launch pad--this was all known going into launch.

The stresses of Shuttle launches routinely deformed the SRBs, pulling them apart at the joints, with hot gasses ("above 5,000 °F (2,760 °C)") seeping through; however, the O-rings would slip out of their grooves and seal the gap. They hadn't actually been designed to do that, but they did, so the specs were modified to account for it and consider it normal behavior.

All well and good in normal balmy Florida temperatures, then, but on the Challenger during the January 28th launch, the slipping and sealing action is thought to have been slowed by the cold hardening the rubber of the O-rings. Before they could seal the hot gasses in at one of the joints on the right SRB, they'd been vaporized.

That in itself might not have been enough to doom the mission, as aluminum oxides from the burned solid propellant actually gathered in the gap at the damaged joint of the right SRB and sealed it. Launch appeared to be continuing normally.

But 37 seconds into launch, the Shuttle was hit by 27 seconds of the strongest wind shear events ever recorded in the Shuttle program's history; they shattered the oxide seal, allowing the gasses to flow freely. By the time the Shuttle was clear of the turbulence, the leak was a jet of flame shooting out of the side of the booster. That lateral jet forced the SRB to start to pull away from the rest of the vehicle, and within ten seconds, this unexpected force, throwing other considerable forces of the launch out of balance, was enough to have torn the craft apart.

It did not actually explode: the large plumes of vapor seen in the breakup were the oxygen and cryogenic hydrogen fuel spilling out of the disintegrating external fuel tank. In fact, the crew compartment pulled free of the rest of the vehicle in one solid chunk, arcing a further five kilometers up through the sky on a ballistic trajectory; it did not begin to fall back to Earth until 25 seconds after the vehicle had broken up.

The compartment was intact, but it isn't known if the crew survived that rise, and then the plunge toward the ocean, or for how long; the last message caught by the voice recorder was pilot Michael J. Smith's "Uh oh" a half-second after the SRB first wrenched to the side under the force of the escaping & burning gas jet. When analyzing the wreckage of the cabin, it was found that some electrical control system switches on one of Smith's control panels had been thrown, possibly indicating he had--futilely--tried to restore power to the detached cabin. Furthermore, three of the four Personal Egress Air Packs--emergency oxygen systems capable of supplying six minutes of breathable air--on the flight deck had been activated, indicating that at least two of the crew members, other than the pilot, had been alive to activate them after the cabin broke off from the rest of the vehicle. But they were only meant to provide air in case of something like noxious gasses in the cabin, and so were unpressurized; if the cabin had lost pressure, which seems likely, then they would have been useless. In any case, there was certainly nothing the crew could have done to save themselves, and the cabin smashed into the ocean at "207 mph (333 km/h)," with a force of "well over 200 g," far beyond what the crew compartment, let alone the crew, could survive.

It's rather shocking to think about--and this isn't even in retrospect, since these ships are still being flown!--but the Shuttles have no ejection system. All previous manned U.S. space vehicles had ejection systems--none of which were ever used--but while multiple ejection systems had been discussed--and at one point even installed--for the Space Shuttles, in the end, they were all rejected as impractical, of limited utility, or too costly. Although I suppose there would have been little chance of an escape system working in the Challenger disaster, when the cabin was tumbling at who-knows-what angle, it's still disheartening to know that there is simply no escape option during a launch procedure.

~~~~~~

Guh still disheartened now that I've written all that. But anyway I hope you'll find the depiction of space in today's A* page to be a bit better, or at least an interesting attempt. I think it's getting somewhere, although I broke some of my own rules on this one, such as using a bit of Gaussian Blur. :P Other than that, the background was pretty much all done with Gimp's airbrush tool at various settings. Oh, except for the larger nearer stars, which are little radial Photoshop gradients.

More storyboards and rejected storyboards for later in this episode! It's a mad, mad tea party you know:

^ For future reference, that one's in the episode 13 gallery, newly available from the "episodes" top menu item.

~~~~~~

Also, as usual I've neglected all week long to invite you to take a look at the latest page of my weekend fairy tale comic, "The Princess and the Giant," which you will find clickably linked from this inviting teaser banner thingy:

And there'll be an even newer page of it going up on Sunday.

Have a nice weekend!

|